Once upon a time, a new technology happened along. It was called radio. Soon enough, some people began plucking wireless transmissions out of the air for their own purposes. One clever young man in Washington figured out how to intercept messages that Navy units sent to one another. “He has represented himself to be at distant naval stations or at sea on warships equipped with wireless apparatus,” a magazine called Electrical World reported in 1907. Back then, this fellow’s actions were not unlawful. They amounted nonetheless to a form of piracy.

Grappling With the ‘Culture of Free’ in Napster’s Aftermath

As radio grew more sophisticated, so did those intent on beating the system. In 1960s Britain, radio pirates flourished on unlicensed stations that broadcast from ships anchored beyond territorial limits. They found eager audiences in young people who tuned in for the latest from the Rolling Stones, the Kinks and the Who. (Talkin’ ′bout my generation.) Then the world went digital. Naturally, pirates tagged along. One of them, the online sharing service Napster, forms the core of this Retro Report offering, the final installment in the current series of video documentaries examining the consequences of major news stories from the past.

Napster Documentary: Culture of Free | Retro Report | The New York Times

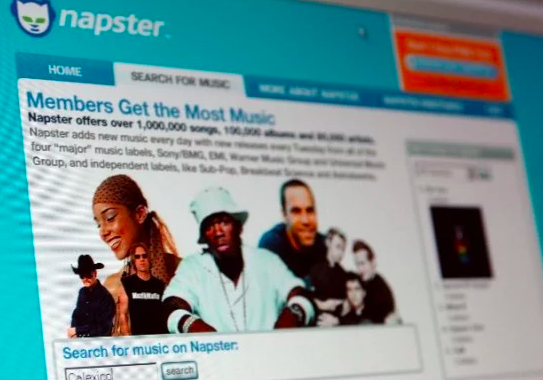

In 1999, a file-sharing program created in a Boston dorm room sent shock waves across the music industry and served notice that a major cultural shift was underway.

Napster is the name given to three music-focused online services. Developed by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker. And it’s Initial release was June 1, 1999; 19 years ago. It was founded as a pioneering peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing Internet service that emphasized sharing digital audio files, typically audio songs, encoded in MP3 format. The company ran into legal difficulties over copyright infringement. It ceased operations and was eventually acquired by Roxio. In its second incarnation, Napster became an online music store until it was acquired by Rhapsody from Best Buy on December 1, 2011.

Napster did not last long, two years. But for a while at the dawn of this century it claimed to have 70 million registered users. It spawned a host of Internet music-swapping providers, more than a few of them falling on the dubious side of the law. Most important, it irrevocably altered not only the way in which Americans absorbed music but also their belief system in what they should pay. The conviction theologically held by many boiled down to a single word: nothing. “You have a generation of people now who expect their music for free,” Greg Hammer, managing director of Red Bull Records, a branch of the energy-drink company, told Retro Report. “It’s very difficult to change.”

The music industry is not alone in coming to terms with altered realities. As every sentient soul surely knows by now, the “culture of free” — words borrowed from the title of this week’s video — has turned the print world upside down, pushing newspapers, magazines and book publishers into a frantic search for financial safe harbors. With the advent of broad Internet use in the 1990s came a notion that information should be free. Never mind that the gathering and transmission of information can be a costly proposition and that (dirty word alert) money is needed if the survival of, say, a newspaper is to be ensured. As with music in Mr. Hammer’s observation, a generation now believes that the written word, whether on processed wood or in pixels, should come without charge.

Napster burst forth in June 1999, the brainchild of an entrepreneurial, 18-year-old computer wiz, Shawn Fanning. His creation enabled anyone with a modicum of tech savvy to share audio files in MP3 format — peer to peer, as it was called. Music lovers could download thousands upon thousands of songs, then pass them on to friends or create albums of their own on compact discs. No one paid royalties. To music companies and some individual artists, this was high-tech piracy and a threat to their fiscal well-being. (It might be noted that the commercial introduction of CDs in the early 1980s delivered its own near-mortal blow to an earlier technology, long-playing vinyl records.) The Recording Industry Association of America sued Napster for copyright infringement. So did a few musicians, like the rapper Dr. Dre and the heavy metal band Metallica.

Not every performer thought of Napster as the enemy. Some who might otherwise have been doomed to oblivion regarded the service as a platform from which they might find listeners and build a fan base. Nor were all economists convinced that one free download equaled one less sale of a high-priced CD; quite possibly, some of them said, people were plugging into music that they would never have paid for.

Gnutella. Mr. Fanning tried his hand at new digital media endeavors, including Snocap and Napster 2.0. Few of those companies were unqualified successes. One thing was certain, though: The culture of free was not going away.

A decade ago, Apple established a new order in the commercial music universe by introducing the iTunes store. From its vast digital warehouse, customers could buy any song they wished, typically for 99 cents. The arrangement was perhaps not ideal for the recording companies and for many performers. Among other things, music albums — fixtures since the ’60s and, in many instances, creative masterpieces — were becoming relics; single-song listening ruled, whether through an iTunes purchase or snatched from the ether via file-swapping networks. Still, for the industry, some money was better than none, and so an iTunes reality beat a Napster world.

Now the music business is in transition once more, reshaped by streaming services like YouTube, Spotify and Pandora. Instead of owning songs, a listener can in effect borrow them from millions of titles made available by these operations. A cultural shift seems well underway, with more and more consumers sensing they no longer need to possess certain physical items, like CDs or books. A reliable Internet connection will do.

Unlike Napster and the like, the streaming services are not engaged in piracy. They are legally licensed, having paid music companies some money. They themselves cash in by selling advertising or, increasingly, by offering subscriptions to customers interested in a commercial-free experience

An independent Napster may be gone, but its impact reverberates, not least in the continuing threat to intellectual property.

The results have been stark. Data from Nielsen SoundScan, a sales-tracking system, show that consumers in this country listened to 70 billion songs via streaming services in the first half of 2014, an increase of 42 percent from the same period a year earlier. Sales of albums, whether on CDs or through digital downloads, declined by 15 percent. Downloads of individual tracks were down by 13 percent

Embrace the change, Silicon Valley types say. But even if one does, it comes at a cost. As CDs fade from the scene, so do stores like Tower Records. Thousands of jobs are lost: workers who make the discs, wholesale buyers, salespeople, stockroom clerks, accountants and others. Substitute work for them is not assured in the digital cosmos. And, thus far, the people who create the music on which others build their fortunes often receive mere rivulets of reward. Not everyone is a Beyoncé or a Taylor Swift (who has removed her entire oeuvre from Spotify to keep it behind a pay wall). Many more musicians are like Zoe Keating, a cellist from Northern California who described her situation in detail last year. Over a six-month period, Ms. Keating’s songs had been played on Pandora more than 1.5 million times; that earned her all of $1,652.74. She had 131,000 plays on Spotify in 2012. She took home $547.71, or less than half a penny per play.

Some industry executives insist that, over time, things will sort themselves out, including how to steer more money to performers. Last month, for instance, YouTube announced plans to generate revenue by giving its users an opportunity to pay a few dollars a month in return for extra features that are not available to those who click on songs at no charge. Royalties to artists, in theory anyway, would thus rise.

In the meantime, some oldsters (talkin’ ′bout my generation again) may derive a measure of comfort from learning that vinyl albums still have life. Nielsen SoundScan reported four million sales of vinyl LPs in the first half of this year, a 40 percent increase from the same period in 2013. Go figure. Hey, maybe you can get a copy of “Revolution 9” from the Beatles’ White Album, and check out for yourself if, when played backward on a turntable, it really does tell you that Paul is dead.

Written By Clyde Haberman – Dec. 7, 2014. Produced by: Retro Report. Read the original story here

The video with this article is part of a documentary series presented by The New York Times. The video project was started with a grant from Christopher Buck. Retro Report has a staff of 13 journalists and 10 contributors led by Kyra Darnton. It is a nonprofit video news organization that aims to provide a thoughtful counterweight to today’s 24/7 news cycle. Previous Retro Report videos can be found here, and articles here.

RetroReport.org – Essays and documentary videos that re-examine the leading stories of decades past.

Retro Report’s mission is to arm the public with a more complete picture of today’s most important stories. We correct the record, expose myths and provide historical context to the fast-paced news of our world today using investigative journalism and narrative storytelling.

A series of short interviews with artists talking about the state of the music industry, a supplement to this Retro Report episode, can be found here.

What the legendary match between a supercomputer and a chess grandmaster reveals about today’s Artificial Intelligence panic.

A documentary that explores the downloading revolution; the kids that created it, the bands and the businesses that were affected by it, and its impact on the world at large.

Director Alex Winter’s documentary recalls the groundbreaking launch of Napster and the legal battles that sank the company. Downloaded focuses on two teenage friends, Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker, who came up with a groundbreaking internet start-up while they were in college, dropped out and moved to northern California to launch their company. If you like what you have been reading and watching, definitely check out Alex Winter’s 2013 film ‘Downloaded’ below. Watch Chapter 1 Here.

Everything is a Remix (Remastered) (2015 HD)

About creativity , “intellectual property” and social evolution.

Nothing is original, says Kirby Ferguson, creator of Everything is a Remix. From Bob Dylan to Steve Jobs, he says our most celebrated creators both borrow, steal and transform.